Zins sweet spot: Sonoma’s Dry Creek Valley may be the key to Zinfandel’s future

Sonoma’s Dry Creek Valley key to Zinfandel’s future

Zinfandel is in many ways California’s most prosperous immigrant – an imported grape of modest origins that made it big in the New World. At the end of its journey to California, Zinfandel found a natural home in Sonoma’s Dry Creek Valley. It’s not a large appellation but Dry Creek claims the highest concentration of first-tier Zinfandel producers of any region in California. Its climate and soils are peculiarly suited to the variety, and now that generations of family farmers have honed their understanding of the grape, it’s clear that Zinfandel is not only the most important grape in Dry Creek Valley’s history, but also the key to its future.

Through the years, the outstanding quality and reputation of Dry Creek Zinfandel allowed it to emerge as Dry Creek’s bread and butter wine. It was often blended with a little bit of Petite Sirah and Carignane to boost the color and tannin, but the base of the blend was always Zin.

“My great-uncle Eugene, or Pete Sr., called Zin ‘the Boss Grape,’ ” says fourth-generation winemaker and grower Ted Seghesio, whose family has been making wine in Dry Creek Valley since the 1950s.

Located in northern Sonoma County, Dry Creek Valley is approximately 15 miles long and about 2 miles across from ridge to ridge. Long and narrow with steep sides, it lies between the cool, coastal Russian River Valley and the hotter Alexander Valley inland. That makes it a climatic sweet spot for growing Zinfandel. In cool years Zinfandel has a hard time ripening in Russian River Valley, and in warm years Alexander Valley Zinfandel can taste baked and raisiny. But the Zinfandel of Dry Creek Valley usually ripens well, full of berries and spice and everything nice.

“If you talk to a typical Napa Cabernet drinker, they may not know Dry Creek Valley, but it you talk to a serious Zinfandel drinker, they know the valley’s reputation,” says Mike Dashe, who owns Oakland’s Dashe Cellars with his wife, Anne. Dashe got his start as an assistant winemaker at Ridge Vineyards, which makes its renowned Lytton Springs Zinfandel from an old Dry Creek Valley vineyard.

Unique and consistent flavors in Dry Creek Zinfandels have played a large part in establishing their reputations. The presence of freshly ground pepper, cinnamon and other spices is a recurrent theme, so much so that the spicy character of Dry Creek Zinfandel has become a textbook descriptor of the variety.

“I’ve always thought of Dry Creek as having one defining characteristic that cuts through all of the fruit,” says Bill Knuttel, winemaker for Dry Creek Vineyard, one of the region’s largest wineries. “The spice to the Zin here is like dried flowers, and it comes from a lot of different vineyards.”

Climate is only part of what arguably makes Dry Creek Valley California’s Zinfandel headquarters. In Dry Creek Valley, unlike in some other parts of the state, most Zinfandel is planted on the benchland hillsides rather than on the valley floor, where vines overproduce and are more prone to rot if fall weather turns damp.

“My dad used to say that most of the immigrants that came over were very poor so they were relegated to buy the hill land rather than the valley floor. They cleared it themselves and were able to plant a few acres and sell the wine,” says Dave Rafanelli, third-generation vintner at A. Rafanelli.

“I don’t think they knew back then that they had actually chosen the best place to grow Zinfandel,” adds Seghesio.

To this day, it’s the abundant benchland plantings of Zinfandel that make Dry Creek Valley Zin such a hot commodity.

“It’s a very narrow valley, so from the beginning you have a higher percentage of hillside vineyards compared to a wider valley,” says Clay Mauritson, whose family has owned land in Dry Creek Valley since the 1860s. “In the early years, people were growing prunes in the valley floor and getting more for them, and people went to the hillsides to plant Zinfandel. We had higher-quality Zinfandel from the very beginning.”

Gallo is the largest landowner in Dry Creek Valley, and its vineyards supply ample grapes for its Zinfandel-fueled Rancho Zabaco and Dancing Bull brands. But the vast majority of the valley’s vineyards are owned by independent growers and wineries. A few own a couple hundred acres and many more control 100 or less. It is home to some 62 wineries, the vast majority of which are family-owned. Of those, 50 produce 10,000 cases of wine or less per year.

Dry Creek may be a sweet spot for Zinfandel, but both the region and the grape have taken a long path from jug wine to respectability.

There is documentary evidence to suggest that California’s first Zinfandel vines originated from a collection of Austrian vine cuttings and were brought to the United States in the 1820s by a New York nursery owner and then carried to California by a Massachusetts nursery owner sometime around 1840.

“Historically, Zinfandel came here as a table grape in the 1850s. The main wine grape at the time was Mission, which made really mediocre red wine,” says winegrower Fred Peterson of Dry Creek Valley’s Peterson Winery. “When people planted Zin and made wine, it was really good. Within 15 years Zinfandel was grown pretty much throughout California.”

During Prohibition, the best growers sustained their vineyards by selling grapes to home winemakers in San Francisco, and Dry Creek Valley emerged from the Prohibition years with a healthy reservoir of mature Zinfandel vineyards. Vineyards grow old only when demand for their grapes is reliable year after year, even through the toughest times. Only those that grew the best fruit endured, leaving Dry Creek with lots of high-quality, old-vine Zinfandel. “You look at pieces of antique furniture and you might think that furniture was built so much better back then, but the truth is that only the good stuff survived,” explains vineyard consultant Duff Bevill.

Today Dry Creek’s old-vine Zinfandel vineyards mingle with younger vineyards planted with carefully selected rootstocks and vine cuttings and farmed using modern viticultural techniques. When old Zinfandel vines die off, Dry Creek Valley is one of the few places in California where they’re likely to be replaced by new Zinfandel vines.

That’s possible thanks to Zin’s long push for respectability. Through the 1970s, consumers drank lots of Zinfandel but often the variety didn’t appear on the label. “My grandfather labeled it ‘California Claret,’ ” says Rafanelli.

It was also the guts of Gallo’s popular Hearty Burgundy. And while California Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay were competing with their French counterparts from Bordeaux and Burgundy, they soared in popularity. Varietal labeling became the rule. California Zinfandel, meanwhile, had no foreign benchmark and wasn’t as well marketed, so it fell out of favor. In the 1980s, it was sweet White Zinfandel rosés that kept Zinfandel’s head above water in Dry Creek and elsewhere. Even if it gave people the wrong impression of the powerful red grape, Zinfandel was finally being mentioned on wine labels.

Finally, in the 1990s, consumers began looking for alternatives to stodgy Cabernet Sauvignon, which helped spur a resurgence of high-quality Zinfandel from Dry Creek Valley, Napa Valley, Lodi and other regions. At the same time, the Zinfandel Advocates and Producers started its wildly popular ZAP tasting, which draws more than 10,000 eager fans to San Francisco’s Fort Mason each January. (This year’s ZAP festival runs from Wednesday to Jan. 26.)

Today there is as much Cabernet Sauvignon as Zinfandel planted in Dry Creek, but much of the Cabernet Sauvignon is sold off to other Sonoma wineries, while the Zinfandel is vinted and bottled by the growers and sold – more profitably – under their own labels. The Boss Grape, Zinfandel, still pays the bills.

For Zin producers, then, these are exciting times. Demand is strong for quality Zinfandel and a strong series of vintages from 2005, 2006 and 2007 is sure to help further boost Dry Creek’s profile.

Of course, with acclaim comes spiraling prices. More and more Zinfandels are climbing into the $30 and $40 price range, including those from classic Dry Creek producers like Rafanelli, Preston, Ridge and emerging stars like Wilson, Mazzocco, Dashe, Mauritson and others. Wineries defend the high price tags, pointing out that – at least in Dry Creek – demand for Zinfandel still outstrips supply. “Some grapes have been overplanted,” says Shelly Rafanelli, who is taking over winemaking duties from her father, Dave, at Rafanelli. “Zinfandel has its little niche and there’s not too much of it, so the prices are hanging in there.”

Just as with Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir, Zinfandel is a grape with devoted followers.

Zinfandel is also one of the most difficult grapes to make into fine wine, which further explains rising prices. It’s prone to rot and uneven ripening so harvesting at just the right moment is an art. “You just have to work with a vineyard for a while to get an idea of how it will ripen,” says Dashe.

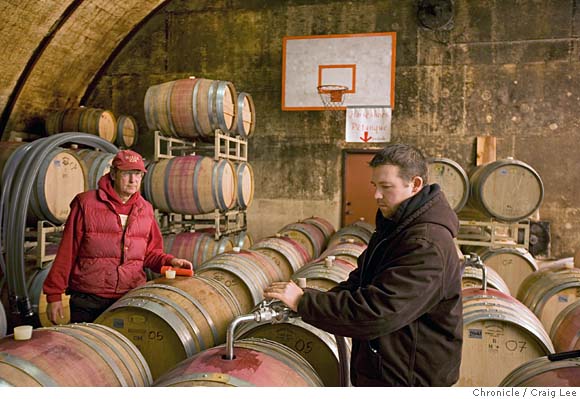

For that reason, experience counts, nowhere more so than in Dry Creek Valley. The valley’s proliferation of family wineries has created a winemaking culture that has several generations of experience with Zinfandel, and that’s undoubtedly one of the secrets of the region’s success.

Today, many are passing the torch to the next generation. Clay Mauritson’s family has owned substantial acreage in Dry Creek since the 1800s, but Clay was the first Mauritson to build a winery and establish a family brand. Likewise, at Nalle, Andrew Nalle is following in his father Doug Nalle’s footsteps, making some of California’s most restrained, fleet-footed Zinfandels, which almost always come in at under 14 percent alcohol. The younger Nalle says it’s easier for him than for his father to drink today’s more potent Zins, but he plans to follow his father in making Dry Creek’s most elegant, long-lived style of Zinfandel.

Most of these winemakers don’t even have formal winemaking degrees, but they’ve all got generations of experience with Zinfandel.

In Dry Creek Valley, that time has been invested. The art of making Zinfandel is passed down from generation to generation, with greater and greater success. For Zinfandel, the Boss Grape, there is nowhere better than Dry Creek Valley.

Road to Rockpile

One of the most exciting trends in Dry Creek Valley in recent years is the emergence of the new Rockpile American Viticultural Area, approximately half of which is included in the Dry Creek Valley AVA. Located in the Northwest corner of the valley on a rocky hilltop overlooking Lake Sonoma, Rockpile’s vineyards offer dramatic views as well as dramatic wines. Zinfandel grown there is deep and highly structured due to slightly cooler temperatures and the diverse rocky soils that keep the berries small and crop yields very low.

Vineyard manager Duff Bevill of Bevill Vineyard Management describes the Rockpile region as “steep and hilly with no flat parts. High altitude and windy, with lower nighttime temperatures. It’s different up there for sure.”

First officially recognized in 2002, Rockpile still boasts less than 200 planted acres. Already the terrific wines made there by Zin luminaries like Rosenblum, JC Cellars, Carol Shelton and Mauritson have given the Rockpile district some fast notoriety.

Styles of Dry Creek Valley Zinfandel

There are strong recurring themes in the Zinfandel wines of Dry Creek Valley. Perhaps the most notable quality they share is the prominence of aromatic spice and dried flowers in the nose, from fresh-ground black pepper to cinnamon, coriander and cardamom, plus a dusty earth note that often appears. Achieving balance in Zinfandel, which is prone to high sugar levels and resulting high alcohol, is tricky. The region’s veteran winemakers, ideal climate and steep gravelly slopes combine more often than not to make wines that retain elegance and balance that you don’t always find in Zinfandel.

Grapes grown on the west-leaning slopes on the east side of the valley can be riper, fleshier and have darker fruit flavors because they get more afternoon sun than grapes from the west side of the valley. Harvest on the east side of the valley can occur three to four weeks earlier than on the other side of the valley, a mere mile away. The northern end of the valley can produce riper wines than the southern end near Russian River Valley, and wines grown in the altitudes of the hillsides generally have more color and tannin – especially true of wines from Rockpile.

Wines from Wilson and Mazzocco, both made by winemaker Antoine Favero, carry high alcohol with remarkable grace. “When people drink my wines they’re surprised that they’re 16.5 percent alcohol. Because the fruit is so big and the tannins are prevalent too, the alcohol doesn’t stand out the way you would think,” he says.

Preston, Quivira, Rosenblum and Amphora also make relatively full-bore Zins, though still graceful and not overblown. For Zinfandels that find a subtle middle ground between rich fruit and good structure, try wines from A. Rafanelli, Mauritson, Dry Creek Vineyard, Bella, Ravenswood, Teldeschi Vineyards, Ridge, Rancho Zabaco and Lambert Bridge. (See The Chronicle Wine Selections, page F4.)

Nalle makes some of the prettiest, most elegant Zinfandels in Dry Creek Valley. They’re wines that emphasize the pepper and dried flower aspects of the terroir, and are food-friendly, but not at all unripe. Peterson is another good label for more restrained wines that seldom push ripeness too far.

Written By

Tim Teichgraeber