The New California is an Old Story

The move from power to finesse in Californian wine is the next big thing, but also a very old story, explains Mike Steinberger.

In case you haven’t heard, the new thing in wine is the so-called New California.

That’s the catchphrase being used to describe a stylistic reorientation in California winemaking – a shift in emphasis from power to finesse, a move away from hedonistic fruit bombs to, well, let’s call them succulent little firecrackers.

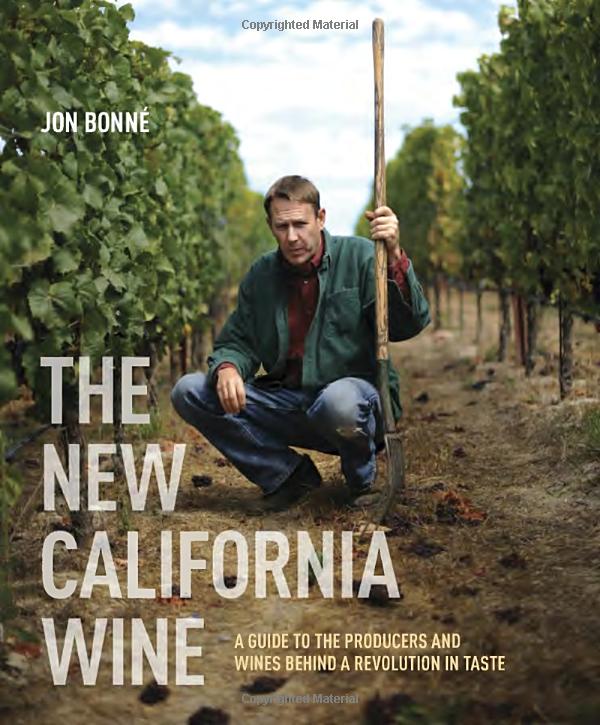

Everyone is talking about the New California, not least because it’s the title of an important new book by Jon Bonné, the wine writer for the San Francisco Chronicle. Something exciting is indeed happening in California – an experimental spirit that is leading winemakers to dabble with obscure grapes, to plant vines in unlikely locations, and above all, to challenge the prevailing wisdom about optimal ripeness and what balance means in the context of California wines.

However, the term New California is a misnomer: the pursuit of finesse is hardly a recent or revolutionary development in California.

In reality, the power versus finesse debate has been raging for years. From the birth of the modern era of California winemaking – let’s peg it to the late 1960s – there was an inherent tension between the Old World sensibilities of many California winemakers and the fact that California could yield levels of ripeness unimaginable in Bordeaux or Burgundy.

The great California wines of the 1970s – the ’71 Ridge Eisele, the ’74 Heitz Martha’s Vineyard, etc – seemed to strike a perfect balance between elegance and thrust. But even those wines provoked dissent. Some people felt that they erred too much on the side of ripeness, and this backlash gave rise to the so-called “food wine” fad of the 1980s, in which grapes were harvested at low brix levels in order to craft wines that put an accent on acidity.

In the mid-1990s, the pendulum swung again, this time in the direction of power. The change came about largely because of the influence of Robert Parker (with an assist from the Wine Spectator’s James Laube, whose preferences aligned with Parker’s), and it was a dramatic shift – the phrase “maximum hang time” became mantra, alcohol levels soared, and extravagant ripeness became California’s signature.

Parker was at the apex of his influence from the mid-1990s through the first half of the 2000s, and because his scores made the market for California wines, producers had a powerful incentive to cater to his whims. Parker wasn’t shy about browbeating winemakers who failed to appease him. In 1999 and again in 2000, he lashed out at the Mondavi family, accusing them of making Old World-style wines that represented a betrayal of the California idyll, which he described as “power, exuberance, and gloriously ripe fruit.” The Mondavis initially rejected his criticism but soon capitulated, hiring Parker’s favorite consultant, Michel Rolland, to assist with their wines.

Judging by the triumphalist, the-Iron-Curtain-has-fallen, rhetoric hailing the New California, you might think that Parker, at the height of his reign, stamped out all dissent and forced winemakers up and down the state to submit to his diktats. Many did join the Mondavis in genuflecting to Parker (and Laube, too – let’s not forget him), but some refused to do so.

Take Jim Clendenen of Au Bon Climat Winery, north of Santa Barbara. He started in the early 1980s with the goal of making Pinot Noirs and Chardonnays in a Burgundian vein. Success came quickly and, for a time, Parker was as enamored of Clendenen’s wines as others were. But by the mid-1990s, the famed critic had done a volte-face: he began criticizing the wines as too lean, and he damned Clendenen with mediocre scores. But Clendenen didn’t budge – he continued making wines in the same style.

Steve Edmunds likewise held firm. Edmunds is the winemaker of Edmunds St. John, one of California’s original Rhône Rangers. His wines have long had a keen following among enophiles who enjoy Rhône varieties rendered in an earthy, elegant style. Parker was once a fan, too.

In 1993, he hailed Edmunds as the “finest practitioner” of Rhône-style wines in the U.S. But by the middle of the next decade, Parker had changed his mind. In 2007, he published a notoriously caustic review of Edmunds’s wines, in which he essentially accused the winemaker of committing viticultural treason. “There appears to be a deliberate attempt,” Parker said, “to make French-style wines. Of course, California is not France, and therein may suggest the problem. If you want to make French wine, do it in France.” It was a broadside that echoed his attack on the Mondavis. But in contrast to the Mondavis, Edmunds refused to stray from his chosen path.

That took some brass ones – Parker still wielded enormous influence seven years ago, and inviting his wrath was a risky thing to do. The saga of Napa’s Mayacamas Vineyards is perhaps instructive.

During the 1970s, Mayacamas made some of the most celebrated wines ever to emerge from California. These Cabernets showed plenty of ripeness, but the alcohol was restrained and the fruit was balanced by brisk acidity and minerality. That remained the Mayacamas style through the ’80s, ’90s, and into the new century. But at some point, Parker became disenchanted with the wines, and he told his readers that Mayacamas was no longer worthy of their attention.

“In the 1960s and 1970s,” he wrote in the 2008 edition of his buyer’s guide, “there was no greater or long-lived Cabernet Sauvignon than that made high in the Mayacamas Hills by Bob Travers. For unknown reasons, the current offerings have nothing in common with those early vintages.” The write-up for Mayacamas didn’t include any scores or tasting notes, which was presumably a measure of Parker’s dissatisfaction.

Mayacamas went being from one of California’s standard-bearers to an afterthought – a wine treasured by those who knew it and liked the style but that pretty much disappeared from the consciousness of the broader consumer market. However, the key point is this: even when Parker was the kingmaker and when ripeness was the undisputed coin of the realm in California, refusniks like Travers, Clendenen, and Edmunds (and Cathy Corison and Mike Chelini and Doug Nalle, to name a few more) kept alive a very different vision of California wines – an aesthetic that valued finesse above all else. That sensibility has now been christened The New California, but it isn’t new; it has been a pillar of California winemaking going back decades.

What is new in California is the ideological climate. With Parker’s influence waning and many consumers tiring of the strapping, high-alcohol wines that he prefers, there is more space for experimentation and stylistic variation. California, you might say, has gone back to the future.