Chemist Alexander Shulgin, popularizer of the drug Ecstasy, dies at 88

Chemist Alexander Shulgin, popularizer of MDMA, says his favorite mind-altering drug is ” a nice, moderately expensive Zinfandel.”

Brian Vastag

Alexander “Sasha” Shulgin, a chemist and psychopharmacologist who introduced the world to the drug MDMA — later called Ecstasy — while creating hundreds of other psychedelic drugs that ultimately provoked a harsh government crackdown, died June 2 at his home in Lafayette, Calif. He was 88.

His death was announced by his wife and research partner of 35 years, Ann Shulgin. He had been in declining health since a stroke in 2010 and had a recent diagnosis of liver cancer.

Known variously as “the love drug,” “empathy” and “Adam” before being advertised as “Ecstasy,” MDMA first spread from Dr. Shulgin’s lab to a coterie of psychotherapists in the late 1970s.

A decade later, the drug rocketed around the world as a recreational high, sparking the rave and club culture and leading to an unknown number of deaths from overheating, impurities and adulterants introduced by unskilled and unscrupulous drug makers.

Dr. Shulgin spent his final years as a revered elder — a psychedelic Gandalf of sorts — traveling to conferences and the annual Burning Man arts festival in the Nevada desert, where he and his wife were praised by self-styled seekers of spiritual enlightenment.

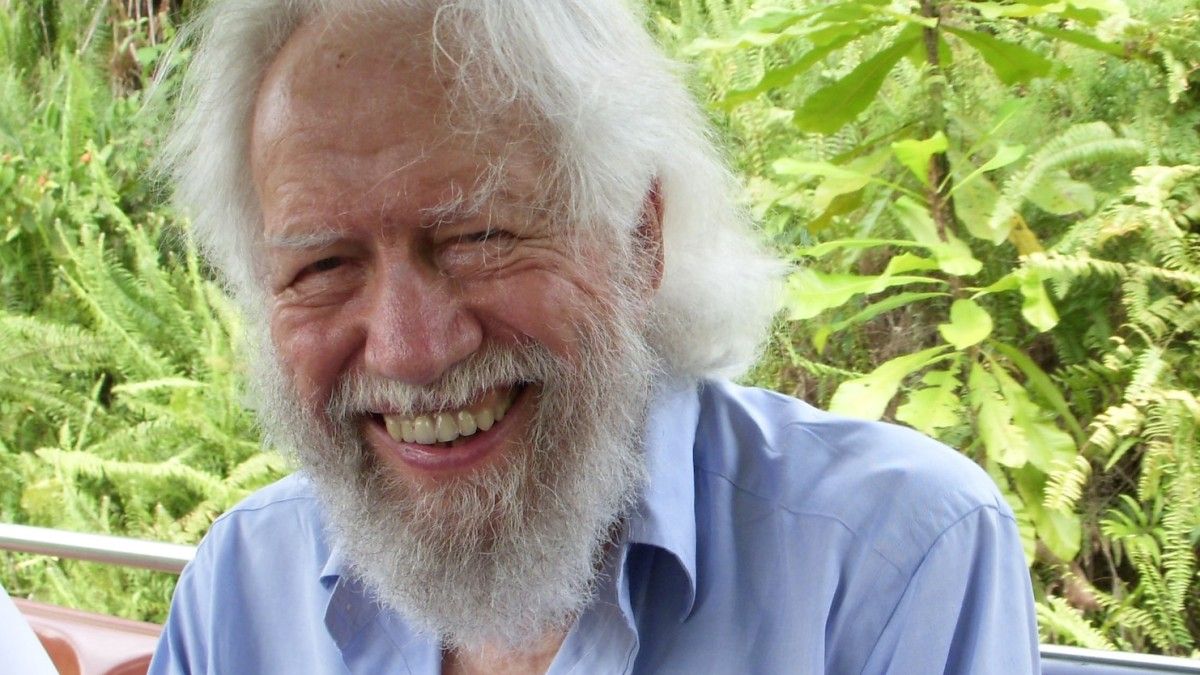

Alexander Shulgin, a scientist who simplified the process for making the drug Ecstasy, in 2007. (Photo by Brian Vastag)

In the last few years, he saw a resurgence in legitimate research on MDMA as academics restarted clinical trials with MDMA as a therapeutic tool, publishing studies showing that the drug can help veterans come to terms with the trauma of war.

“He was very depressed once MDMA was criminalized,” said Rick Doblin, president of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, which funds clinical trials of MDMA and LSD. “Sasha always felt these drugs didn’t open people up to drug experiences, but opened us up to human experiences of ourselves.”

In 1985, with first lady Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No” campaign in full swing, federal authorities banned MDMA with an unusual emergency action. It was placed on the Drug Enforcement Administration’s most restrictive list of dangerous substances, those “with no currently accepted medical use” and a high potential for abuse. A multimillion-dollar anti-Ecstasy media blitz followed, and Dr. Shulgin was entangled in the country’s decades-long drug war.

“There’s no reason I should be Dr. Ecstasy,” he said after a 2005 New York Times magazine article gave him that title. “That’s not the name I gave anything. I call it MDMA.”

The renaming of the drug and an explosion of recreational use “in essence destroyed the medical value,” he said.

As a scientist at Dow Chemical in 1965, Dr. Shulgin stumbled on a compound patented by the German drugmaker Merck in 1912 that was a close chemical cousin to amphetamine, or speed. Finding no apparent use, the company abandoned the drug, leaving it to languish in a chemistry journal until the U.S. Army experimented with it in the 1950s.

Although Dr. Shulgin did not invent MDMA — its full chemical name is 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine — he concocted a relatively easy method for making it. He first tried MDMA in 1976.

“I feel absolutely clean inside, and there is nothing but pure euphoria,” he wrote in his 1990 book “PiHKAL” (for “Phenethylamines I Have Known and Loved”). “I have never felt so great, or believed this to be possible. I am overcome by the profundity of the experience.”

Dr. Shulgin also felt such a deep connection to the people around him — a “universal love” — that he later gave a small vial to a psychotherapist friend, Leo Zeff, who provided the still-legal drug to several thousand therapists around the world,.

“Once the therapists started using it, whew, it was in demand,” said Bob Sager, a retired DEA agent and longtime friend of Dr. Shulgin’s.

The love drug quickly became a menace, according to the DEA’s history of MDMA. An enterprising seminary student in Dallas named Michael Clegg branded it “Ecstasy” and began selling up to half a million pills per month.

Despite the DEA’s ban, Ecstasy’s popularity exploded, and by 2001, an estimated 8 million people in the United States had tried it. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration reported more than 200 deaths involving the use of Ecstasy between 1994 and 2001, although most were related to accidents or the use of other drugs.

Amid the tumult, Dr. Shulgin continued to advise the DEA and testify as an expert witness at trials. He analyzed street drugs under a DEA license, but a federal raid on his backyard lab in 1994 severed that relationship.

An escalating legal and chemical war followed, with Dr. Shulgin cranking out new psychedelic drugs faster than the DEA could ban them. In 1986, the DEA tried a new tack to get ahead of Dr. Shulgin, passing the Federal Analogue Act, which sought to ban drugs not yet invented if they were hypothetically similar to already-banned drugs.

Dr. Shulgin responded by spinning his chemistry even further afield. In his dusty, cluttered lab, with orchestra music as a backdrop, he poured his efforts into hundreds of brown glass bottles, each labeled in Sharpie pen with a unique chemical formula — drawings Dr. Shulgin delighted in calling “dirty pictures,” in response to the government’s war on his work.

Despite his impish delight in tweaking authority, Dr. Shulgin also built unlikely connections to mainstream culture via his participation as a violist in the exclusive Bohemian Club, an annual gathering of business and political leaders in the northern California woods whose members have reportedly included President George H.W. Bush, former secretaries of state Henry Kissinger and Warren Christopher and newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst.

Alexander Theodore Shulgin as born June 17, 1925, in Berkeley, Calif. His parents were teachers, and he won a scholarship to Harvard at 16. He dropped out to serve in the Navy during World War II, then completed a biochemistry PhD in 1954 at the University of California in his hometown.

At Dow, Dr. Shulgin invented a line of successful biodegradable insecticides before his psychedelic eureka moment arrived in 1960 in the form of a small pile of white powder: mescaline, the active ingredient in peyote and other cactuses

With Dow’s blessing, Dr. Shulgin began tinkering with mescaline’s molecular structure, creating the first of hundreds of new psychoactive drugs, which he published in scientific journals. But by 1966, as an LSD-fueled countercultural wave brought on an overwhelming federal backlash, Dow realized it was in the awkward position of owning a fistful of now-demonized mind-bending compounds.

Dr. Shulgin left the company, moving to “the Farm,” a plot of family land in the Berkeley hills, where he spent the balance of his life visualizing, and then creating, variations on dozens of psychedelic themes.

Even as the psychedelic antiwar movement of the 1960s and ’70s raged, Dr. Shulgin preferred the quiet of his exacting experimental work — the counterculture’s Thomas Edison to Timothy Leary’s blaring P.T. Barnum.

With each new chemical creation, Dr. Shulgin performed a meticulous “bioassay” — testing the drug on himself in escalating doses, then bringing in his wife, Ann. If the drug proved safe and interesting, the couple shared it with a “research group” of eight to 10 close friends.

Dr. Shulgin kept detailed notes, which he published in a series of books, starting with “PiHKAL.” Each chemical recipe included ratings on the “Shulgin scale,” up to “Plus Four”: “a rare and precious transcendental state, which has been called a peak experience.”

In a 2007 interview with this reporter, Dr. Shulgin said he had achieved only “two or three” Plus Four experiences among an estimated 4,000 psychedelic trips in his lifetime.

With a modest income from Social Security and a cellphone tower on his property, Dr. Shulgin and his wife asked their extended psychedelic family for donations in recent times to pay escalating medical bills.

Dr. Shulgin’s first wife, Nina Gordon, died in 1977. Their son, Theodore Shulgin, died 2011. Survivors include his wife of 32 years, the former Laura Ann Gotlieb; and four stepchildren.

During a conference of psychedelics enthusiasts in 2007, Dr. Shulgin lamented that he was often asked to name his favorite mind-altering drug. Despite devoting his life to plumbing the depths of human consciousness, he answered, “Probably a nice, moderately expensive Zinfandel.”

CORRECTION: This obituary has been revised to correct errors. Dr. Shulgin’s first marriage, to Nina Gordon, did not end in divorce. They were still married when she died in 1977. The obituary also erred in reporting that Dr. Shulgin first tried MDMA in 1967; it was 1976, his family said.